A Global Clavichord

A Trading World

If we take another look at the map you will notice the ship icons all around Western Europe. These point to the main ports with which Hamburg traded during the 18th century.1

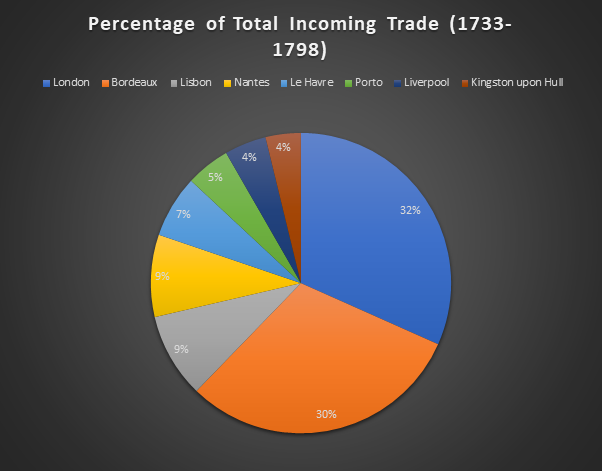

By looking at the pie chart, we see that the largest trading partner ports were all in Western Europe. However, many of the materials used in the clavichord do not come from Europe but arrived at these western European ports through European imperial and colonial networks.

Activity

Take a closer look at the map. From which port would it have taken the longest time to travel to reach Hamburg? Rank your answers from 1 (shortest time of travel) to 7 (longest time of travel).

For each journey, guess how long the journey would have taken using a ship in the 18th century.

Check your answers using this website which allows you to calculate the distance and time at sea. Use 5 knots as the speed, given that we know that an average ship in the 18th century traveled at an average of 4-6 knots.

Interconnected Art

All across the clavichord, we can see a style of painting on the red (vermilion) background called chinoiserie. What is chinoiserie? Why was this style used on this clavichord? What can the chinoiserie of this clavichord tell us about the world at the time?

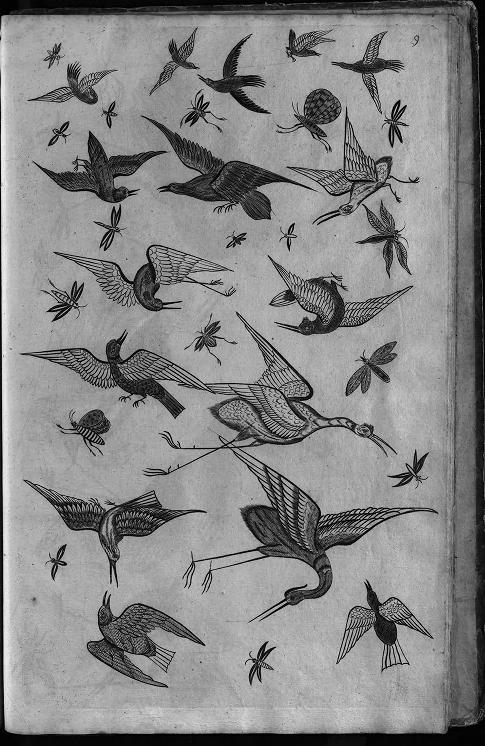

Chinoiserie is a western design style that was popular in Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was a fanciful interpretation of different Asian styles, in which Chinese, Japanese or Indian styles were combined to create an exotic fantasy world. In 18th-century Britain, China was perceived as a mysterious, faraway place. Although trade between the two countries had increased over the 17th and 18th centuries, access to China was still restricted and there were few first-hand experiences in the country. Chinoiserie drew on these exotic, mysterious preconceptions. Objects featured fantastic landscapes with fanciful pavilions, sweeping lines of roofs resembling Chinese pagodas, fabulous birds, and figures in Chinese clothes.2

You can see some of these birds in the image of the clavichord above. We know from comparing different musical instruments from the time that these birds were probably traced. At the time, there were books like J. Stalker & G. Parker’s A Treatise of Japanning and varnishing (London, 1688), which explained how to draw and paint in chinoiserie styles.3

Activity

Using the above image, trace or draw a bird or insect of your choice.

If you fancy a challenge, try to draw or trace the image below.

A view from East to West

Just as chinoiserie was a popular style in Europe, there were artistic influences from Europe in China and Japan. While very few people would have ever seen these opposite sides of the world, it was through art that an imagination about what these far away parts of the world might look like was being spread.

Commercial and religious interactions were the main channels through which Chinese and European art objects and ideas were exchanged. Especially in the courts of Europe and China at the time, there would have been considerable interest in the other. China at the time was ruled by the Qing dynasty (1644-1912). In the Qing court, European culture was part of the daily life experience. European stylistic elements can be found in Qing court paintings.4

An important way in which interaction with Europeans influenced Chinese artwork was through adopting some European styles and techniques. The image below is from a 1681 Chinese booklet discussing lenses. The artist has used a reference to European artwork, seen especially well in the design of the houses. The image and the booklet provide evidence of cultural exchange between China and Europe as early as the 17th century.4

Below we can see an image from Huang Qing Zhigong Tu (Chinese: 皇清職貢圖; Collection of Portraits of Subordinate Peoples of the Qing Dynasty), it is an 18th century study of the peoples with whom the Chinese Empire came into contact, including some western European nations with which trade was conducted.

貢 圖 or “Qing Imperial Illustrations of Tributaries”.

Bibliography

1. Pfister, U., ‘Great Divergence, Consumer Revolution and the Reorganization of Textile Markets: Evidence from Hamburg’s Import Trade, Eighteenth Century’, Economic History Working Papers, (266, 2017).

2. vam.ac.uk. Accessed 15.04.2021. V&A · Chinoiserie – An Introduction (vam.ac.uk).

3. Whitehead, Lance, ‘Clavichords of Hieronymus and Johann Hass’ (Edinburgh, 1994).

4. Wang, Cheng-hua. ‘WHITHER ART HISTORY? A Global Perspective on Eighteenth-Century Chinese Art and Visual Culture’. The Art Bulletin, (96, 2014), 379–94.